Auto Correct is a handy feature of iOS which immediately fixes your typing mistakes by replacing any incorrectly spelt words with ones that are correctly spelt. Due to the size of the iPad and iPhone keyboards, and the lack of tactile feedback, it’s a lot easier to make typing mistakes than on a physical keyboard. So Auto Correct is quite useful on these devices.

But there’s a problem: Auto Correct doesn’t always get it right. Given an incorrectly spelt word, there are usually several possible candidates for replacement, and no software is intelligent enough to guess which one you meant in all cases. The word you typed may even be valid, but just absent from the system’s dictionary.

What you often end up with is documents or text messages in which the words all have correct spelling, but not necessarily the correct meaning. In some cases this can lead to some very embarrassing results — many of which have been thoughtfully archived for public reference at one of my favourite websites, damnyouautocorrect.com.

In the early testing I did with UX Write, the most annoying aspect by far was iOS’s built-in Auto Correct mechanism. I tried turning it off for a while, but I found that my documents were filled with lots of typing mistakes, so I decided that on balance, it was better to leave it on. But I still wasn’t happy with it. Even though it does give you the opportunity to cancel a replacement, you have to do so immediately, which I found a major interruption to my writing flow.

So I’ve come up with a way to make it better.

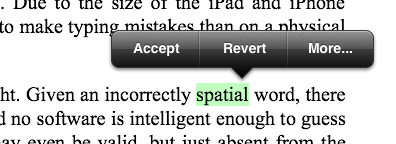

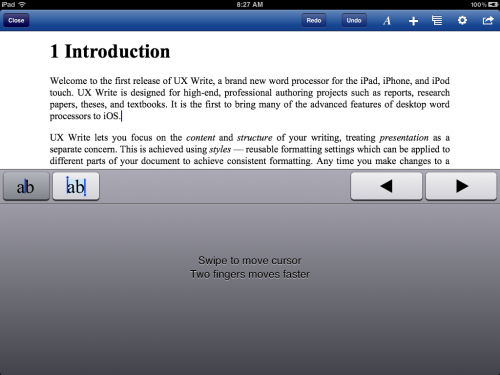

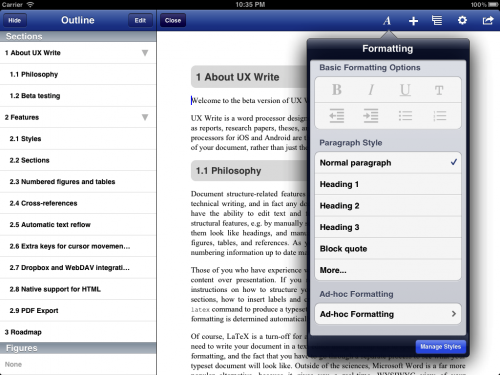

In UX Write, when you make a typing mistake and Auto Correct “fixes” it for you, it highlights the replacement. You can continue typing, and then some time later go back and review your text for all the highlighted replacements and accept or revert each one. Tapping on a highlighted replacement brings up the following menu:

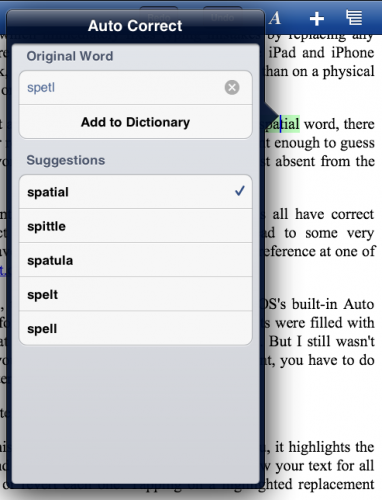

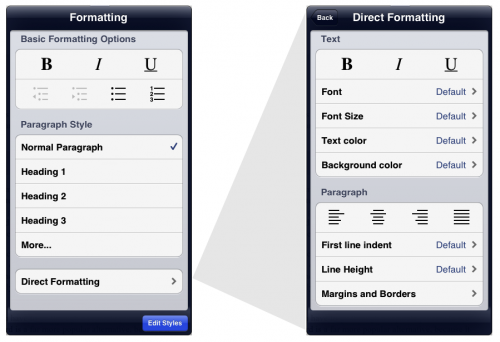

“Accept” indicates the replacement is correct, and that the program should perform the same replacement in the future automatically without highlighting it. “Revert” changes the text back to what you originally typed. “More” brings up another menu with a list of alternative spellings, and an option to add the original word (which you can edit) to your custom dictionary:

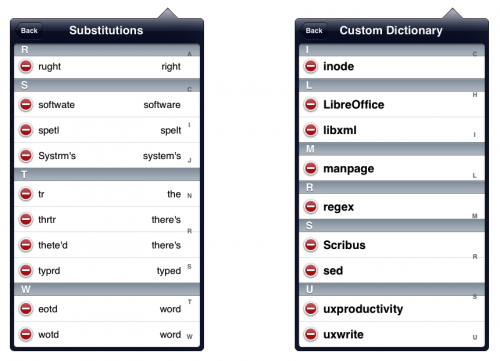

Both the custom dictionary and list of previously-accepted substitutions are accessible from the settings menu. If you accidentally add a word to the dictionary or accept a substitution that you didn’t mean to, you can easily go the appropriate list and remove it.

The only limitation of this in the first release of UX Write is that it only works for US English. I’m planning on adding application-wide and document-specific language settings, so you can have the correction mechanism work in any language that iOS supports.