How does the saying go? Time flies when you’re either having fun, or working on software to translate between different file formats. Something like that, anyway.

Word support is taking longer than expected to get completed, so I wanted to give an update on where things are at. Given the importance of this release, and the fact that many people are now relying on UX Write for their daily work, I’m not going to hurry to push this out – I’m going to wait until it’s truly ready and has had sufficient testing. I know a lot of people are waiting for Word compatibility to arrive, but I believe it’s better for me to wait until the update is at a sufficient level of reliability, than to release early and risk causing problems for people.

So here’s a summary of what is and isn’t in place currently:

Text and basic document structure

Plain text, obviously the simplest aspect of the file format, is fully implemented (and has been for a long time). The representation of text and basic structure in the .docx format is well-thought out:

- A document consists of a sequence of paragraphs and tables

- A paragraph consists of a sequence of runs, each of which contains text with different formatting properties

- A table contains a grid of cells, each of which contains a sequence of paragraphs and (nested) tables

That’s a nice and simple structure. There’s a little more to it, but essentially this matches what HTML does. HTML actually allows a little more flexibility in the structuring of paragraph content (you can have nested runs, for things like bold text, color and font changes etc), but each HTML paragraph is easily transformed into a “flat” representation that corresponds directly with Word’s model.

Styles

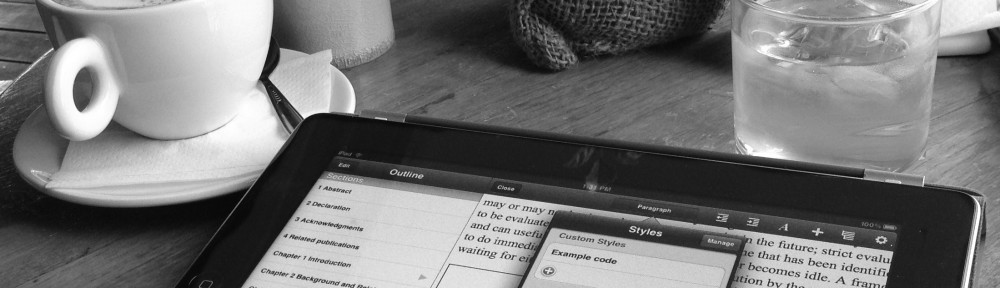

Styles are almost fully supported. Word supports three primary types of styles: Paragraph styles, Character styles, and Table styles. UX Write’s user interface currently only allows you to edit paragraph styles (this will change in a future version, but not in 1.1.0), however all character and table styles are maintained and displayed during editing.

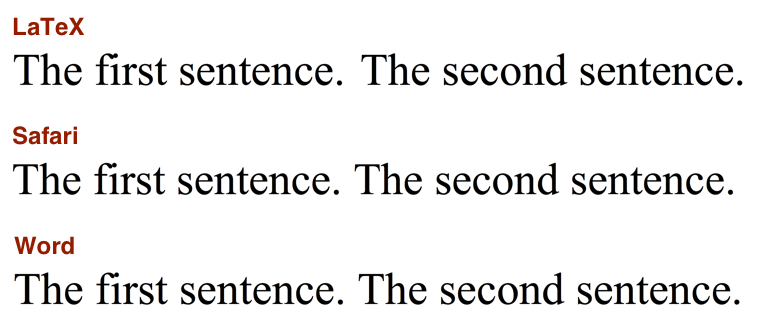

Since the document is translated into HTML and maintained as such during editing (as described in my previous post), all formatting properties are represented using CSS, the stylesheet language used on the web. CSS supports the vast majority of formatting properties present in .docx, with a few minor exceptions such as double-strikethrough and different types of underline. In general, the way the document appears in UX Write will be the same as in Word (with the notable exception of pagination and page layout; see below), though there are a few minor quirks.

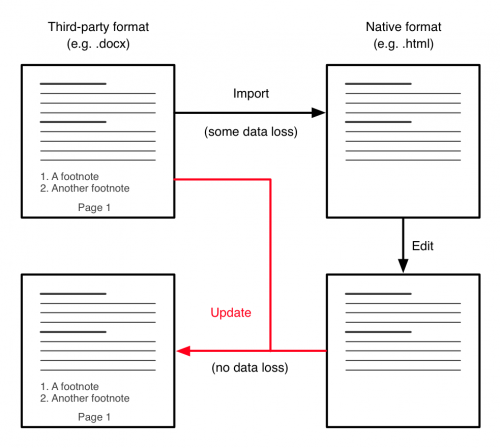

If you’re using one of the few formatting properties in your document that can’t be expressed in CSS, these will be maintained in the document, due to the bidirectional transformation technique used to save documents.

Supported formatting properties

The following properties are supported for both direct formatting and styles:

Paragraph properties

- Borders (thickness, color, and line type), configurable for each side

- Background color

- Text alignment (left, center, right, and justify)

- Left and right margins (indentation)

- Separate indentation for the first line (both positive and negative, or “hanging” indents)

- Top and bottom margins (spacing between paragraphs)

- Line height (spacing between lines in a paragraph)

Text properties

- Bold

- Italic

- Underline

- Strikethrough

- Font name

- Font size

- Text color

- Background (highlight) color

Tables

Table structure (rows, columns, and merged cells) is fully supported. There’s no user interface support for adjusting column widths or merging and splitting cells yet (again, this will come later), but the table structure you see in UX Write will be the same as in Word.

One very powerful feature of .docx is the variety of table formatting options it supports – you can set properties not just for all the cells in the table, but for the first and last rows, first and last columns, even and odd rows, even and odd columns, as well as the cells in each corner of the table. Word itself contains an extensive range of pre-defined table styles with various nice appearances.

These aspects of table styles are not yet supported in UX Write, but I’ve figured out a way of representing all the various options in CSS, so it’s going to be possible to achieve this. In the future, I will be adding the ability to edit table styles within the style manager, enabling you to set all of these properties. Since they can be expressed in CSS, these options will also be available when working with regular HTML documents as well. For now however, tables are formatted using only plain, black borders.

Lists

This was a very challenging one. Word has a completely different concept of what a list actually is, compared to that used by most other formats, including HTML, ODF, and LaTeX. The translation between the two models is far from straightforward, and while I’ve been able to cater for the typical use cases, there are a few uncommon cases that can’t be expressed in HTML.

In HTML, ODF, and LaTeX, a list is an object containing a sequence of items, and each item is an object containing a sequence of paragraphs, tables, or other lists. Thus there is an explicit notion of the items being contained within a list.

Word, strictly speaking, doesn’t actually support lists. What it does support are numbered paragraphs, which are simply normal paragraphs which have an optional numbering definition associated with them. A numbering definition specifies a counter, which increments each time it is used, and a format for the number at each level of indentation (such as arabic or roman numerals, or uppercase/lowercase letters).

With a simple list that has only one paragraph per item, each paragraph is adjacent to the next, and all have the same numbering definition. This can easily be translated into a HTML list, by simply creating an item element (<li>) for each paragraph, and placing those inside a single list element (<ol> or <ul>).

With a list that contains multiple paragraphs inside an item, things start to get a bit more complicated. All paragraphs after the first in a given item have no numbering definition associated with them, so it’s impossible to tell which list item they’re associated with simply by looking at the paragraph itself. What the translation algorithm has to do is go through all the paragraphs in the document and keep track of what the most recent numbering definition it saw was. This determines which list item subsequent paragraphs are placed under.

The algorithm has to be careful when doing this however, as it needs to distinguish between a paragraph that is part of a list item, and a paragraph that comes after the list. The only way to do this is to look at the indentation level of the paragraph:

- If the paragraph starts at the same horizontal position as the first paragraph in the list item, then it’s part of the same item.

- If its horizontal position is to the left of the current list item, this means that it comes after the list in question.

So the translation algorithm must look at the indentation level of each paragraph to determine whether it is part of the previous list, or comes after the list. And in the case of nested items, it also has to determine which of those items it is part of.

Another complication is that because there’s no containment relationship between different items in a given list (remember, there is no explicit concept of a “list” in Word), it’s actually possible to have interleaved lists, like this:

1. First item in list A

2. Second item in list A

i. First item in list B

ii. Second item in list B

3. Third item in list A

iii. Third item in list B

It’s impossible to express this in HTML. What will happen in this situation is that the first two items in list B will be placed in a nested list inside list A, and the third item from list B will be put into a separate list that comes after A. Unfortunately this will result in the numbering starting again from i. I don’t think this is likely to be very common though, and I can’t think of a situation in which you would actually want to do something like this (though if you can think of one – let me know).

The main types of numbering formats that CSS supports (decimal, decimal-leading-zero, lower-roman, upper-roman, lower-alpha, upper-alpha) and bullet points (disc, circle, and square) are all supported, and are translated correctly in both directions between their equivalents in Word. Numbering formats involving multiple levels (e.g. 1.1, 1.2, 1.3) in the case of nested lists are not supported, though I may be able to find a way to address this in a later update.

The argument that lists should be represented in a hierarchy as opposed to a flat sequence of paragraphs may seem pedantic and obscure, but it suddenly becomes very important when you try to do outlining. Spend two minutes using OmniOutliner and you’ll very clearly see the opportunities brought about by representing things hierarchically, like the ability to expand and collapse individual items, move entire nested lists around, and so forth. I have plans to expand the outline feature in UX Write to incorporate lists, in addition to the current support for headings.

Automatic numbering

Numbered headings in Word use the same mechanism of numbering definitions as lists, except that the numbering definition to be used is specified in the heading style, rather than as a direct formatting property on the paragraph itself. The default template in Word has numbering off by default, but you can turn it on in Word by going to the style editor, then Heading 1, then Format -> Numbering, then Outline numbered, and select one of the seven different types of outlining formats. In UX Write I’ve simplified this down to a “Numbered headings: on/off” in the settings menu. I’ll add the ability to customise this later.

The style translation algorithm detects styles named “Heading1” through “Heading6” and translates them into CSS style declarations using HTML’s <h1> to <h6> elements. For each of these styles, it looks to see if there is a numbering definition set, and if so, sets the appropriate CSS properties to assign numbers to headings automatically.

Tables and figures are handled differently. Rather than using numbering definitions, Word instead uses field codes placed in the adjacent caption (if present), which increment a named counter, such as “TABLE” or “FIGURE” (though sadly this purely internal name can differ depending on the language in which the document is written – even though it’s never made visible to the user). Because the names of counters aren’t guaranteed to be the same in all documents, the translation algorithm examines what type of object is above each caption, and uses that to decide whether to number it as a table or figure. As with headings, CSS counters are used for making these visible in the document.

Cross-references

Word supports multiple types of cross-references, e.g. just referencing the section number or title, or in the case of a table or figure, including the label and number (e.g. “Table 1”), or even the entire caption (e.g. “Table 1: 2012 Revenue”). UX Write uses hyperlinks (<a> elements in HTML) to represent cross-references, and custom javascript code to generate the text of the cross-reference. I have defined custom class names for each different type of cross-reference, and the javascript code inspects the class name of an <a> element when updating cross-references to decide what should be displayed as the reference text.

Word represents the targets of cross-references using bookmarks, in contrast to HTML, which uses id attributes on the target element. A bookmark specifies a range of text in a document, and has a name associated with it which is used in any cross-references that point to it. The difference between these and id attributes is that they can appear anywhere in the text, and even span multiple paragraphs.

In determining the id attribute to set on headings, tables, and figures, the translation algorithm searches for the closest bookmark within the object and uses its name as the id attribute. Going in the other direction, if a new heading, table, or figure has been added, it generates a new bookmark in the appropriate position.

Note that in UX Write, cross-references are updated in real-time as you modify the titles of headings, or the captions of figures and tables. They are also updated whenever the associated number changes, such as if you insert a new section above an existing one that’s a target of a reference. Thus, you don’t have to go through the manual process of doing a select all and then pressing F9 (on windows) or Cmd+Option+Shift+U (on the mac) every time you want to ensure all the cross-references and the table of contents are up to date, as you have to do in Word.

Images

Images are partially supported at the moment. Existing images in documents will display in UX Write, and you can add new images from your photo library or current directory in the same manner as you do already. I’ve still yet to implement the ability to replace an existing image with a different one, and to properly translate the size of the image.

Word has two completely different ways of representing images in a document. I actually didn’t realise this until someone sent me a document to test with that had originally been created with an older version of Word and then converted from .doc to .docx. Modern versions of word use the DrawingML language to represent images, while older versions used a separate language called VML. From what I understand, the reason for keeping VML support in .docx was to make it easier to translate from .doc files to .docx, but I’m of the view they should have gotten rid of it completely and had Word automatically translate from VML to DrawingML itself, leaving only one way of representing images. Still, for documents converted from old versions of Word, I’ll have to add support for images represented using VML as well.

One really major befit of .docx over HTML is that you can embed images directly in the document, instead of storing them as separate files. If you’ve been creating HTML documents in UX Write that contain lots of images, you’ve likely noticed your folder in the file browser fill up with lots of image files which you’d rather not see intermixed with your documents. When using .docx, this will become a thing of the past, and you’ll just see the document itself.

Hyperlinks

HTML uses a really simple model for hyperlinks – it just has an element of the form <a href=”http://www.uxproductivity.com”>UX Productivity</a>, and that’s it.

In Word, you have a hyperlink element, which references an “external resource” using a numeric identifier. The text of the hyperlink is stored in the main document, but to find out the target it’s necessary to look at a separate XML file within the word package (which is represented as a zip file containing all images and other associated files). This particular file is known as a relationships file, and contains, among other things, a mapping from the relationship identifier specified in the main part of the document to the actual target URL of the link.

The translation process resolves the external reference in this manner and generates the nice, simple HTML representation given above. Going the other way, it takes the URL, and sees if there are any existing entries in the relationships file with this same URL. If there is, it reuses this same identifier. Otherwise, it generates a new identifier, adds a relationship for that URL, and then uses that new identifier when creating the hyperlink element in the main document content.

Change tracking

This is partially supported, but only to the extent that tracked changes are preserved and displayed in the HTML file, but cannot yet be accepted or rejected. Additionally, changes you make to the document in UX Write itself are not yet recorded (this will come post-1.1.0).

Word represents tracked changes as specially marked text which is either an insertion, deletion, or a formatting change. The first two of these can be directly represented in HTML using the <ins> and <del> elements, which UX Write applies a default style to so that the content of <ins> elements are displayed in blue, and the contents of <del> elements are displayed in red strikethrough. Right now, you can see both of these in the converted document, and even edit them. It’s likely this will be how it stays for the 1.1.0 release, but the next step here is to add the ability to accept/reject changes, see who made them, record changes that are made to the text in UX Write, and show or hide the deleted changes and insertion highlights.

Word’s model of change tracking is really a poor man’s version control, and there are immensely better ways to do it. I’ll be supporting this model for compatibility purposes, but I’m firmly of the view that version control systems like Subversion and Git are really the way to go. Software developers have used these systems for a very long time; in my case, I have a subversion repository containing all the code for UX Write, and as of this evening it contains a total of 4,164 different versions of the code – each one representing a change that I have made, such as adding or tweaking a new feature, or fixing a bug. I also have comments that I’ve written attached to each version, describing what has been changed and why.

I can go back and retrieve any of those 4,164 different versions, or compare any two of them to see exactly what changes have been made. If I had other people working on the project with me, I would also be able to use this to coordinate with them so we have an “authoritative” version of the code, and have multiple people working on the same piece of code with the ability to merge in their changes. This goes far beyond what Word offers and I plan to explore options to integrate this level of flexibility into future versions of UX Write – though this is an issue I’ll get to much later.

Pagination and page layout

One final point I should mention, and that is very important to understand about UX Write, is that it uses a continuous model of layout with reflowable text. This model is inherited from the underlying web technologies it is based on – every document you edit in UX Write is literally a web page, and is displayed in exactly the same way as it would be in a web browser. In fact, UX Write uses the same layout engine, WebKit, that is used by both Safari and Chrome.

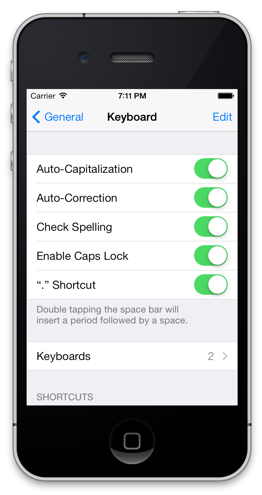

You can’t do page breaks on the web. Every web page is one long piece of content, and you move between different parts of it by scrolling up and down. Additionally, the width of each paragraph depends on the width of your browser window (at least, on well-designed sites); this feature is especially important for phones and tablets which have smaller screen sizes than regular computers. Reading an A4 PDF document on an iPhone or iPad mini involves a lot of squinting and/or scrolling, and really isn’t a pleasant experience. Because of its basis on web technologies, and the fact that UX Write is designed for the small screens present on the iPhone and iPad, it always adjusts the page layout in a suitable manner to make it easy to read, and even lets you choose a scaling factor to make the text larger or smaller, depending on your preferences and vision quality.

If you’re coming from Word, you might find this quite jarring. UX Write is really only WYSIWYG in the sense of what you see is what you get in a web browser, but not what you get in print. During editing there’s no way to see where page breaks will be placed in your document, and you can’t rely on paragraphs being a specific width, because someone reading your document might be using an iPad mini, or even simply rotate their full-size iPad from landscape to portrait, which changes the width of the page.

This approach reflects the philosophy of HTML and LaTeX that content is of primary importance, and layout secondary. Your ideas, your words, and the way you organise them is what you pour so many hours of effort into – what it looks like when you finally publish it is important, but a separate concern that can be dealt with in the final stages before publication. I’m aware that not everyone may agree with this approach, and that’s fine – I’m not trying to cater for every possible usage scenario. In the case of UX Write, I’ve decided to focus on this way of doing things based on the authoring approach I learnt while working in academia, and I consider this approach the right one for many other types of writing as well.

Having said this, I have some ideas about how I might be able to address page layout capabilities in the future, at minimum including the ability to specify explicit page breaks. There are a number of complexities in achieving this, but I’ll be looking into this at some point in the future.

Summary

Wow! You got through all that? Congratulations, and thanks a lot for your interest! As you can see, there are a ton of complex issues here that I’ve addressed over the last few months, which is why it’s taking so long, and why I’m being so careful about making sure this all works reliably before doing a public release.

It’s tempting, from an end-user point of view, to think of word documents as rather simple things that can just be edited easily and passed around – which they are, if you’re only using Word. But since Microsoft haven’t released Word for the iPad yet (and I’m not convinced they ever will, despite persistent rumours), using this wonderful device to do the writing you normally do on your PC or Mac requires someone else to come in and fill the gap. That’s me.

Rather than trying to produce an exact clone of word, I’ve tried to address all these challenges in a way that fits in closely with modern, industry-standard web technologies and caters well for the mobile form factor, as well as providing a powerful environment that makes it as easy as possible to work with the structure of your document. On this last point, I have a bunch of ideas about how to leverage the structured editing approach to provide a range of different ways of navigating and working with the high-level organisation of your documents. But those will have to wait for another post.

As always, comments are welcome.